It is a fact that we do not have any of the original documents for the writings that compose the New Testament. Nor do we have any 1st or 2nd generation copies of these texts. So just how faithful to the original are the current copies we have today? Is it true that there are thousands of errors in the text? And that our New Testament bears no resemblance to the original? Or has it come through this process relatively unscathed? Or somewhere in between?

This is really an issue for every manuscript that comes to us from antiquity. All of them are hand-copied; usually many generations removed from the original. This issue really has little to do with the inspiration or inerrancy of the original texts. It has more to do with the reliability of human scribes and the ability to reconstruct ancient texts from the copies we have today.

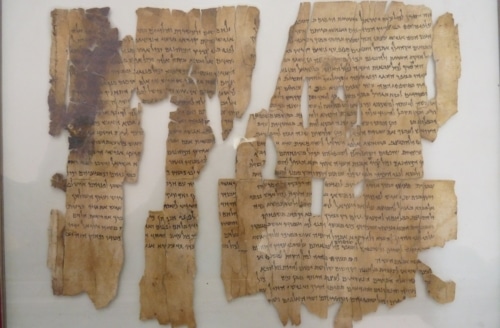

Copying Ancient Texts

In the days before the printing press, any time you wanted to make a copy of a document, whether it be a short note, a letter, or a book, the copying was done by hand. This was a time-consuming task with a great deal of opportunity for error. There were two primary ways that the copying occurred. You might have a solitary scribe who would have the book to copy open in front of him, along with a blank scroll. He would read a section from one and then write it to the other until the copy was complete. The other method was for one person to read aloud the text to be copied. There would also be one or more scribes writing down what they heard. This was useful for making multiple copies.

I imagine that most folks have actually participated in both of these copy methods. You might have copied a recipe, a short quote from a book, or someone else’s notes from a lecture. You might have also written down a verbally given phone number or email address. And just how accurate was your copy?

It can hardly be helped; copying large sections of text will introduce changes in the text. Seldom will the original and the copy be identical, at least if they are of any significant length. Misspellings, transposing words, and skipping or duplicating sections are all common copying errors. Reading back over the copy and comparing it to the original will catch a lot of the errors. But many will still sneak through.

Error Propagation

Errors, once introduced into the text, will generally propagate through subsequent copies. Some errors, like spelling, may be corrected when found, although it may be corrected to the wrong word. As a document goes through multiple generations of copying, the number of copy errors will increase.

How many copy errors have occurred in the New Testament over the years? That is really impossible to say, although you may have heard figures as large as 400,000. But that number is very deceiving. Since there are thousands of manuscripts that are used to accumulate that number, it wouldn’t take more than a handful of errors in each one to come up with a pretty big number. And the vast majority of those errors are simple spelling or transposition errors.

Textual Criticism

Textual criticism is a bad word for some folks, although I suspect that is mostly because they do not know what it is. In essence, textual criticism is the process of comparing the existing ancient manuscripts with each other to work toward producing something that is as close as possible to the original work. This is used on all ancient documents and has become pretty refined over the last few decades. The output of this process, at least for the New Testament, is a Greek edition of the texts that is as close to the original as possible. And then this Greek edition is used to produce our modern translations in a variety of languages.

Corrected Manuscripts

Generally, this Greek edition will include any alternate readings that might be in question, and many modern translations include these alternates in their footnotes. Perusing one of the modern translations, like the NIV, you can see how many places where it was not clear what the original probably looked like. Looking at the footnotes will generally show the variation. And what you will discover is that there are actually not that many of them; and none that really have any doctrinal significance.

So, thanks to the work of scholars using textual criticism, we have in our possession today English versions of the New Testament that are very similar to what was written by the original authors. But wait; is it not possible that significant changes were made early on, prior to the manuscripts that have been preserved? While that is certainly possible, the odds are really against it.

What about Early Changes?

Pick any New Testament book, say Romans. Paul wrote this letter while in Corinth and sent it on to Rome. It was not long until individuals and groups would want a copy of this letter for their own use. So, over the next few years, a number of copies would be made of this letter. And as each of these copies is dispersed geographically, additional copies are made from those original copies. And as time and dispersions continue, even more copies are made. Now, nearly 2000 years later, we collect all of the copies of this letter we can find and discover that there are no substantial differences in any of them. Interesting!

But what if an early copier made significant changes to the original? What would it take for all of the copies that we have today to have been made from that changed copy? If the only copies ever made from the original had the change, then that is all we would see. But if unchanged copies were also made, then we would end up with two distinct versions of the original, each itself being copied and passed down through the generations. And we should see both of these ‘versions’ in the manuscripts we have available today. But we don’t. The only way to avoid that would be if the proponents of one version managed to eradicate all competing versions; itself a monumental task if the competitors had gained much traction.

Conclusion

The best evidence we have today is that our New Testament is essentially the same thing as was written during the middle of the first century. That in itself does not make it any truer than the Iliad or the Odyssey. But it is a powerful argument against those who claim that the New Testament is the product of the 4th century, written to promote the agenda of the Roman church. Thanks to textual criticism, I can have confidence that what I read today is what Paul and the other New Testament authors wrote 2000 years ago.