So which version of the Bible is best? Which one should you choose to do your daily reading and study from? Or is there even a best one? There have been countless articles written on this topic over the years. And they often reach different conclusions. The intent of this post is to share my thoughts about how to choose the best translation for you.

The Translation Type

If you are using an English Bible, or any language other than the original, you will be dealing with translation issues. The Old Testament was mostly written in Hebrew, while the New Testament was written in Greek. While it would be wonderful if there was a one-to-one correspondence for every word in Hebrew, Greek, and English, the reality is that there is not. Choices have to be made as to how best to translate from one language into another.

Formal Equivalence

Some translations attempt to keep the translation as close as possible to the form that it had in the original language. This includes, as much as possible, a direct translation of the individual words and sentence structure. But since vocabulary and sentence structure varies across languages, a direct translation would be very difficult to read. So the translations using formal equivalence will modify the sentence structure to make it more readable in English. In addition, some of the more challenging language idioms may be changed for readability purposes.

The KJV, NKJV, NASB, and CSB are examples of translations that attempt as much as possible to translate in a more formal fashion.

Functional Equivalence

Other translations do not adhere as rigidly to the original form of a passage. Instead, they focus more on producing a functional equivalent. These translations attempt to reproduce the message and intent of the Scripture without necessarily producing a translation that is as close in language as possible. Some expressions in the original language don’t make much sense when directly translated. So more contemporary expressions with meanings as near as possible are used instead.

The ESV, NIV, and GNB are examples of translations that use a more functional approach.

Paraphrase

There is a third type of translation, commonly called a paraphrase. These are not really so much translations as they are English versions that carry the message of the Scripture but are told in contemporary terms. Paraphrases are generally easier to read, but not as useful for a more in-depth study of the Scripture.

The Message and Living Bibles are examples of paraphrases.

Manuscript Families

There are thousands of partial and complete Greek manuscripts of the New Testament. And few of these manuscripts agree completely on the text they contain. The vast majority of the differences between them are minor scribal errors; misspellings, inserted, omitted, or reordered words. These differences are understandable when you realize that all of these manuscripts were hand copied. And that there were many generations of these hand-copied manuscripts. Each copy is subject to potential scribal copy errors.

As time went on, the copies produced in a specific location would not vary much. But when compared between distinct locations, the differences between the copies would become greater. Scholars today, in comparing the many manuscripts, have identified between three and five distinct ‘families’ of manuscripts. The two most important of these for Bible scholars are the Alexandrian and Byzantine families.

Byzantine Family of Manuscripts

This family of manuscripts is centered around Asia Minor and contains far and away the largest number of manuscripts; somewhere in the order of 5000. These manuscripts date as early as the 5th century, although most are more recent.

In the early 16th century, Erasmus, a Roman Catholic scholar, compiled the known manuscripts into a single Greek text. Over the years, he revised his work a couple of times, and others produced similar consolidated texts. It is worth noting that all of these consolidated texts were produced by comparing known manuscripts and attempting to produce what the authors thought would be the original. This involved attempting to identify scribal errors and what the text would have been before the error.

The King James Version

In the early 17th century, the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible was produced. While this was not the first English translation, it quickly became the most popular. This version was produced based on the work of Erasmus and a couple of other men. Their work was compared, and the most common reading made it into the KJV.

Sometime after the KJV was finished, the Textus Receptus (TR) was produced. This was the Greek text that was chosen by the KJV translators. It became the standard Greek text of the New Testament for 200 years. But since its production, many older manuscripts have been discovered, but not incorporated into the TR.

Alexandrian Family of Manuscripts

A second important family of manuscripts was produced around the Egyptian city of Alexandria. While there are only a few hundred of these manuscripts, they are generally much older than the Byzantine family. Some of these manuscripts date back to the early 2nd century.

In recent years other Greek texts have been produced that use these old Alexandrian manuscripts, as well as those of the Byzantine family. Like the work of Erasmus, these Greek texts are produced by comparing the existing ancient manuscripts to try and determine what the original text would have been; a process known as textual criticism. These texts, like the Nestle-Aland, are used by most of the modern English translations, such as the NASB, the NIV, the CSB, and the ESV.

These more modern Greek texts generally give more weight to the Alexandrian manuscripts than they do to the Byzantine manuscripts. While the rationale is debated, it is generally felt that the older manuscripts are more reliable. So even though there are vastly more of the more recent manuscripts, the fewer but older manuscripts carry more weight in the translation process.

Differences in the Manuscript Families

I grew up reading the KJV and was rather shocked when I started reading the NIV; discovering that familiar passages in the KJV were either missing or relegated to footnotes in the NIV. And I know that I am not alone in the confusion that this causes.

It is common for those who advocate the KJV to accuse the more modern translators of intentionally removing critical passages from the Bible. But the reality is that some passages, like the ending of Mark and the story of the woman caught in adultery, are simply not found in the oldest manuscripts. They would appear not to be a part of the original text but were something added by scribes during the copying process of the Byzantine manuscripts.

But it is worth pointing out that none of these additions/subtractions have any real impact on the doctrine of the church. Whether you use the KJV or the NIV, the doctrine it contains is the same.

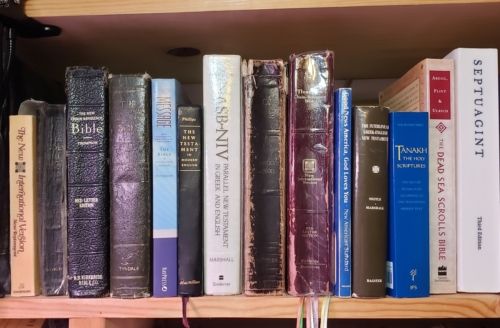

Format

When I became a Christian nearly 50 years ago, the only choice I had for reading the Bible was to either purchase a printed copy or invest in a box of tapes and listen to someone read it to me. But that has changed recently. Digital Bibles have become very popular. I frequently read the Bible on my laptop, my Kindle, and my phone. And most of my study happens on one of those devices. No matter where I am, I have access to my Bible. And not just a single translation. I have half a dozen different translations on my phone, and many more available if I have an internet connection.

Online Bibles

I have found two different types of digital Bible. One is the online Bible. I primarily use Bible Gateway for this. There is a large number of translations to choose from, in a variety of languages. It is easy to search for passages, words, and expressions. And its basic functionality is free. There are also a large number of study aids available for a modest subscription. The primary downside to it is that it requires an internet connection. If you are traveling, or otherwise disconnected, it is not available.

Installed on Your Device

The other format is one that is installed directly on your digital device. I use Olive Tree, although there are a number of other sources. This format has the advantage of always being available, but many of the translations and other resources have a one-time cost associated with them. Most of the translations, and some of the resources are inexpensive, but some are quite pricey. What I like most about this, besides being always available, is that it is easy to share notes and highlights across devices. The notes I take on my laptop are available when I am out in the mountains, and vice versa.

The Downside

There is one major problem I have with online Bibles. And it is purely a personal one. I find it less convenient to put my finger on a page and then explore supporting passages. It is certainly doable with online Bibles. But I find it much easier with a printed copy. I suspect that has more to do with my age than anything. It is how did it for many years prior to the advent of digital Bibles. And it is what I am comfortable with.

But that does not prevent me from using online Bibles extensively. Without question, I spend more time on my phone/kindle/laptop reading and studying than I do with a printed copy.

Resources

One of the issues that you might face with specific translations is the availability of study aids. Most commentaries, concordances, and other study tools are either tied to a specific translation or are referencing one. For commentaries, that is not generally a big deal. But it is for concordances and dictionaries. Because of the great amount of effort involved in producing a printed concordance, they are only available for a limited number of translations.

The KJV probably has the largest number of printed references, simply because it has been around the longest and has a large following. The NIV also has quite a number of specific study tools, but others will be lacking in this area.

But, when using digital Bibles, the need for a printed concordance pretty much goes away. You will be able to search for words, or expressions, across any Bible that you have available.

A Word About Study Bibles

There are also a number of what are called ‘Study Bibles’. These Bibles have commentary or other study notes built into them. These work well for many people. But I am not overly fond of them. I have found that it is sometimes hard to recognize the difference between the actual Scripture, which is God-breathed, and the associated notes, which are not. Just because they are side by side does not give them equal weight. If you use a Study Bible, please make every effort to observe that distinction.

Recommendation

So which English translation of the Bible should you use? In the end, I don’t believe it matters all that much for our general reading and study efforts. Apart from those produced by the Jehovah’s Witnesses, or others, to promote a specific non-orthodox theology, they are all good.

The most important aspect of picking a translation is to choose one that you will read. Readability is really the most important issue. If you will not read it, or cannot understand it, then it really makes no difference how good it is. Bible Gateway is a good online source where you can choose from hundreds of translations. Find one that is meaningful to you, and that you will read, and then use it. Over time you may find that you will change to a new translation. And you may discover that using multiple translations works well for you. But, in the end, pick the one that you will read and use it.

Jared,

Would you consider commenting on the more modern translations of the Bible. I believe the Voice9Now getting old, I guess) and the Passion Translation(a controversial work to be sure) might be worthy of your time. Bible thinker.org may be a worthy link for your readers. Mike Winger is doing an excellent job. Please check it out when you have the time

I do not know who Jared is, unless it is somehow a massive misspelling of “Ed”.

I have not heard of either of the two translations you have mentioned, so cannot really say anything about them. I may look them up later as time allows.